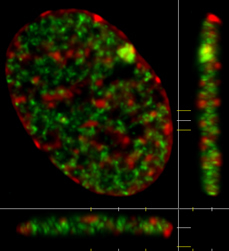

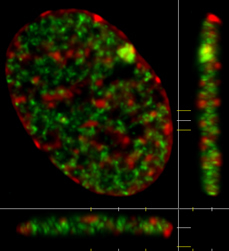

Light microscopy allows the visualization of chromatin and nuclear bodies within the interphase nucleus. While some of these structures are visible using transmitted light (conventional light microscopy), most are not. Fluorescence microscopy allows such structures to be visualized in living and fixed cells. Live cell fluorescence microscopy typically employs fluorescent protein tags which are conjugated to a protein of interest by designing a gene that codes for the fusion of the fluorescent protein tag with the protein of interest. These synthetic genes are then introduced into cells where they generate fluorescent versions of the protein. In fixed cells, it is more common to use antibodies. Antibodies can be generated that recognize specific features that are unique to a protein of interest. The antibodies can be tagged with a fluorescent molecule directly or indirectly. The indirect technique is more common and involves detection of the first antibody with a second, fluorescently labelled antibody, that was generated to recognize the first antibody. The fluorescence can be directly visualized using a fluorescence light microscope. It is common for more than one fluorescent marker to be studied in the same cell. For example, the image in the upper left corner shows a cell that has been stained with an antibody directed against monomethylation of lysine 20 on histone H4 (green) and counterstained with DAPI (red), a fluorescent dye that binds to DNA |